Archive File Formats

mstay / Digital Vision Vectors / Getty Images

Archive files, like Working files, are of two types: originals and derivatives. Originals may be raw files, camera-derived DNG files, JPEG files or possibly TIFF files. Derivatives may be DNG files made from proprietary raw, or any other second-generation rendered file types made from camera originals.

In general, archiving camera originals is recommended, with the possible exception of replacing proprietary raw originals with DNG files. dpBestflow® also recommends archiving master files and preserving their layers when present. You may also want to archive derivative files such as those prepared for printing or delivery.

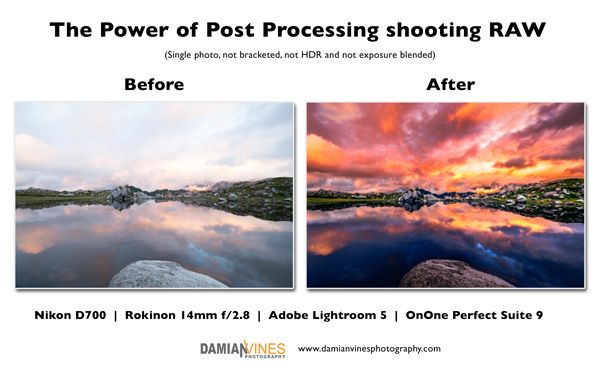

Proprietary RAW

Proprietary raw files have all the advantages of a digital negative: more control over the rendering process, greater bit-depth, and widest color gamut. They may be processed many times over and in a wide variety of software.

Another advantage of raw files is that they are typically only one third the size of uncompressed rendered files such as TIFF. This compact size is due to the fact that the raw data hasn’t been converted to three-channel color and the raw data has lossless compression (or optionally a visually lossless compression scheme).

Small size is maintained even for files that have had parametric image edits, since PIE edits are just tiny text files — usually saved in XMP format. The question is, are they a good archive format?

The main disadvantage to proprietary raw as an archive format is the proprietary and undocumented aspect of these unique and multiplying formats. As we have seen with a wide variety of other proprietary technologies, it becomes inevitable that some, if not most, of these formats will become unsupported as the cameras that made them retreat into the past.

While you may not continue to own these older cameras because you replaced them with new and better models, you will likely want to access the image files these cameras generated long into the future.

You may well hope that your children and grandchildren will be able to have access to these images as many may have recorded significant family events.

DNG

![]()

The DNG format preserves the original raw sensor data just the same as the proprietary raw files. Nothing is left out. DNG is a safer archival container for several important reasons. The first is that it is a documented format. Its specification is openly published and how DNG files are constructed is openly shared with other software vendors.

The second reason is that, unlike any other raw format, DNG contains a file verification tool known as a “hash” that can tell if the raw image data remains unchanged and uncorrupted. This hash only references the raw image data, so a DNG file can be processed an infinite number of times and the XMP instruction set(s) and embedded JPEG preview(s) can be redone an infinite number of times, but the underlying raw data does not change, so it can continue to be verified forever.

One disadvantage of DNG has nothing to do with the format itself but has to do with the number of software vendors that choose to support DNG. Since not all do, DNG files cannot be processed in every possible raw file processor out there, especially the camera manufacturer’s software.

DNG can, however, contain even the proprietary raw file within the DNG container, so if this is a concern, you can choose to save your DNG files with the proprietary raw files embedded. The file verification hash will then also protect the proprietary raw data as well as the DNG raw image data.

This, in fact, is currently the only way to verify proprietary raw files. DNG files can sometimes be smaller than proprietary raw since DNG uses a very efficient lossless compression scheme on the raw image data. DNG files can be the same size or slightly larger than proprietary raw if they contain full size JPEG previews. DNG files can be twice the size of proprietary raw if the proprietary raw file is optionally embedded.

TIFF

TIFF files are considered by some to be the best archival format since it is a standard documented format likely to be supported long into the future, and is of the highest quality formats when saved with either no compression or lossless compression. The drawbacks to TIFF format are due to it being a fully rendered file. Consequently, TIFF files are much larger than raw files, especially when saved as 16-bit and/or layered files.

Additional drawbacks to rendered file formats are that any pixel edits result in loss of image data, or come at the price of saving an additional layer. Even fairly small adjustment layers take up considerably more space than the very tiny XMP files that are saved with raw files.

PSD

![]() We hesitate to add PSD to the list of archival file formats. We certainly wouldn’t get any support from some quarters. However, we don’t think that Adobe is going to discontinue support for PSD anytime in the near future. That being said, PSD is no longer the clear choice for creating and saving layered master files since TIFF now can save everything that can be saved in PSD format. There is another problem with using PSD for layered master files: the RLE (run length encoding) compression the PSD format uses can make for slightly smaller saved layered files if you turn off the Maximum File Compatibility function. Unfortunately this feature will make PSD files unusable by other applications, especially Lightroom and Media Pro. However, when the Maximize File Compatibility is turned on, layered PSD files can end up being much larger than layered TIFF files.

We hesitate to add PSD to the list of archival file formats. We certainly wouldn’t get any support from some quarters. However, we don’t think that Adobe is going to discontinue support for PSD anytime in the near future. That being said, PSD is no longer the clear choice for creating and saving layered master files since TIFF now can save everything that can be saved in PSD format. There is another problem with using PSD for layered master files: the RLE (run length encoding) compression the PSD format uses can make for slightly smaller saved layered files if you turn off the Maximum File Compatibility function. Unfortunately this feature will make PSD files unusable by other applications, especially Lightroom and Media Pro. However, when the Maximize File Compatibility is turned on, layered PSD files can end up being much larger than layered TIFF files.

PSD does have two advantages over TIFF for creating and saving master files: layered PSD files are somewhat quicker and more efficient to open and save compared to layered TIFF files and, for some, use of the PSD format for master files and TIFF for flattened output or delivery files can be used as an at-a-glance organisational tool.

JPEG or JPG

Standard JPEG is only a good file format for archiving if your camera originals are JPEG or if you want to keep a JPEG version of your raw and derivative files online. JPEGs are a much better fit with the current pricing and bandwidth available with commercial online storage vendors.

JPEG2000

JPEG2000 has many advantages over standard JPEG as an archival format. Unlike the standard, baseline JPEG, JPEG2000 offers a fully lossless option. JPEG2000 also incorporates “smart decoding.” This feature enables a decoding application (or plug-in) to access and decode only the required portion of the code stream. This means a single JPEG2000 image can supply multiple, reduced-resolution versions of the original. These might include specific file sizes, and/or a high-quality, high-resolution view of a specific portion of the image. This makes JPEG2000 an excellent format if you require the ability to smoothly zoom, pan and rotate images.

Creating compressed images that contain different quality levels allows master images in an archive to supply multiple derivatives, saving time and bandwidth. This makes an image archive much more efficient. In addition to this array of output options, JPEG2000 can handle very large images, at least up to a terabyte.

JPEG2000, unlike standard, baseline JPEG, supports high-bit-depth (up to 16 bits per channel vs. 8 for standard JPEG) and high dynamic range images. JPEG2000 also underpins the MJ2 and JPM formats for motion images (each frame is a JPEG2000-compressed image) and compound images (images, graphics and text).

These additional features make the JPEG2000 format a potentially valuable option for archiving film, video and historical materials. Photographers who are sold on archiving TIFF files might consider using JPEG2000 for more efficient storage. Many cultural heritage and digital preservation communities use it as the basis for their collections. Unlike photographers, these institutions are less concerned with improved rendering options over time. Their focus is preserving a specific rendering intent in the best way possible coupled with the most efficient storage and delivery options. JPEG2000 does these things well. The unanswered question is whether this “niche” adoption of JPEG2000 will ensure its long-term viability as an archival format.

Some of the cultural institutions finding JPEG2000 to be the best current solution for their archiving needs include The Library of Congress, the Harvard University Library, Library and Archives Canada, Chronicling America website and the Google Library Project.

Format Obsolescence

A major challenge with regard to the preservation of digital image files is the long- term readability of file formats. This is especially true if they are proprietary, which describes most camera makers’ raw formats.

Camera makers have already orphaned some proprietary camera raw formats, and we are only a few years into the process. The sheer number of raw formats, many if not most rewritten with every new camera launch, and the fact that they are undocumented, makes it unlikely that all of these formats will be readable decades from now.

In addition to the proprietary raw problem, other image formats are unreadable on newer operating systems. One of the more shocking format failures is the Kodak Photo CD format. Although Kodak addressed the issue of media permanence, it was all for naught, as there is no longer any application support for their proprietary format. Many museums and other archiving institutions ended up having to convert thousands of these discs to other formats and storage media before all the contents became unavailable. There are many more examples of data locked in obsolete formats that are unreadable.

While converting raw image data to JPEG or TIFF is one strategy for avoiding image format obsolescence, the lossy nature of JPEG and the large size and fixed nature of TIFF are problematic. Converting to a standard raw format is a better choice for image archives.

Currently, Adobe DNG format is the only candidate. Keep in mind, even DNG files may need to be migrated to a subsequent DNG version or a replacement format as yet unknown.

An important feature of the current DNG specification is that all data is preserved. Even data that is not understood or used by Adobe or third party software is preserved.

Although it is too early to tell how successful it will be, the Phase One EIP format may offer another path. It uses the open ZIP format to wrap up the raw image data with processing instructions and any applicable lens cast correction data. Unfortunately, these processing instructions are only read by Phase One software with no guarantee that work done in a current version will be honored in a subsequent version of the software.

The Adobe DNG format, on the other hand, has forward and backwards software compatibility built in.